DB here:

The first edition of Film Art: An Introduction rolled into an unsuspecting world in 1979. Its butterscotch jacket enclosed 339 pages of text and black-and-white illustrations. It was, I think, the first film studies textbook to use frame enlargements instead of production stills. It was definitely the first to argue for a systematic aesthetic of cinema integrating principles of form (narrative/nonnarrative) with style (techniques of the medium). Our goal, of course, was to enhance the readers’ appreciation of the range and power of film as an art form.

Not that there wasn’t a lot of room for improvement. Across three publishers–Addison-Wesley, then Knopf, and finally McGraw-Hill–the book has gained subtlety, precision, bulk, and color images. It now has a suite of online supplements in the form of aids for teachers and video clips for student reference, and the website you’re now visiting. Then there’s our streaming series on the Criterion Channel.

Not that there wasn’t a lot of room for improvement. Across three publishers–Addison-Wesley, then Knopf, and finally McGraw-Hill–the book has gained subtlety, precision, bulk, and color images. It now has a suite of online supplements in the form of aids for teachers and video clips for student reference, and the website you’re now visiting. Then there’s our streaming series on the Criterion Channel.

The core of our efforts remain the ideas and information we explore in the text. That material, happy to say, has found support among teachers, scholars, and writers of other textbooks. Through their suggestions and criticisms, we’ve had four decades to refine what Kristin and I initially set out, and on the eleventh edition Jeff Smith joined us to make things even better.

What’s new about this twelfth edition? Of course, we’ve updated it. We incorporate examples from Get Out, Son of Saul, mother!, Moonlight, Guardians of the Galaxy, Tiny Furniture, Inside Man, Wonderstruck, Dunkirk, Fences, Manchester by the Sea, Baby Driver, The Big Sick, Hell or High Water, Hostiles, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, The Blind Side, Opéra Mouffe, My Life as a Zucchini, Kubo and the Two Strings, Lady Bird, Birdman, The Lost World: Jurassic Park, Tangerine, A Ghost Story, Snowpiercer, The Grand Budapest Hotel, and other recent titles.

One of the biggest changes involves the addition of an analysis of social and political ideology in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. This detailed look at Fassbinder’s melodrama of prejudice replaces our study of masculinity and violence in Raging Bull. That earlier piece will be posted for free access on this site, joining analyses from earlier editions on this page.

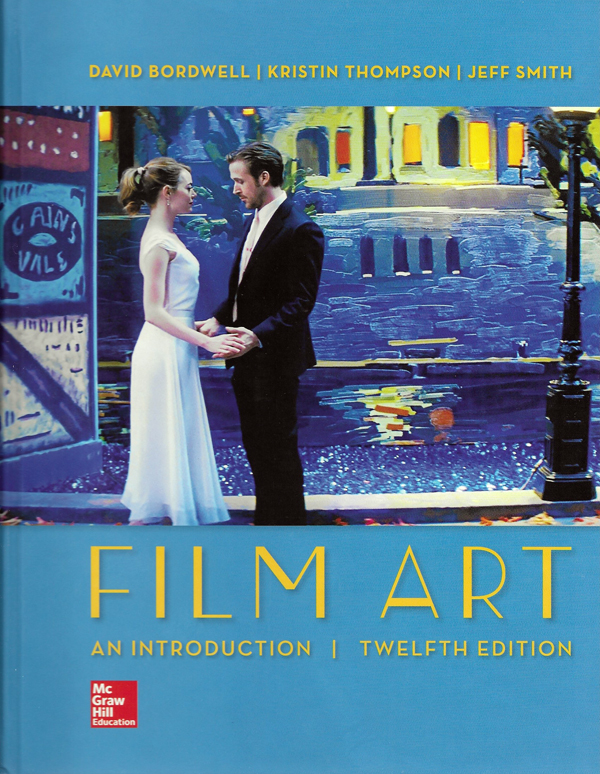

The most evident difference, signaled on the cover you see above, is a new case study of how a film gets made.

Production: The hows and whys

The book’s opening chapter,”Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business,” matters a lot to us. We try to provide concrete, systematically organized information about how people work with technology and within institutions to implement the techniques we’ll survey in later chapters. At the same time, our discussion of production, distribution, and exhibition tries to show how filmmaking institutions shape creative choices about form and style. Perhaps because we try to make those choices down-to-earth, we’ve been pleased to find that Film Art is used in film production courses.

For several editions, Michael Mann’s Collateral served us well as a model of how decision-making in the production process shaped the final film. We thought, however, it was time to refresh that chapter, and La La Land provided us rich opportunities. We had already written blog entries (here and here) about aspects of the film, but we wanted learn more about how it had been created.

Made by a director not much older than our students, La La Land was perfect for a book that tries to be both up-to-date and sensitive to film history. From the burst of ensemble energy in the opening traffic jam to the parallel-reality ballet at the end, Damien Chazelle’s film was both contemporary and classical, what Kristin calls “a modern, old-fashioned musical.” We thought it would help students see that a young filmmaker can draw on tradition while staying firmly in our moment.

The film’s production decisions were well-documented, so we were able to trace four areas of creative choice. By considering the film’s mise-en-scene, camerawork, editing, and sound, we could set up the major stylistic categories to come in later chapters. For example, Jeff could point out unique features of Justin Hurwitz’s score.

We were lucky to get guidance from Damien himself. He reviewed our analysis, and then went far beyond the call of duty. He came to Madison to talk with our students (chronicled here). He sat for interviews with the Criterion Channel on Jean Rouch and Maurice Pialat. He did three Q & A’s. He even took snapshots with his fans.

And Damien energetically helped us secure rights to the cover image, a process that all writers of film books approach with fear and trembling. In short, he proved a total mensch. The fact that he had already read our work when we first contacted him encouraged us in the belief that we might be helping young filmmakers find their way.

Film Art wherever you go

Film Art is now available in a variety of formats and prices. The print edition is now a looseleaf, unbound one. Bound copies still circulate for rental. Students may also rent or buy the e-book edition, which comes packaged as a digital resource called Connect. It’s possible to merge some of these alternatives. The various options for getting the book are charted here.

The Connect package includes teaching aids for the instructor (self-tests, quizzes) and access to thirty-six film extracts, courtesy of the Criterion and Janus companies. There are also four fine videos on production practice by our colleague Erik Gunneson.

As I discussed at exhausting length when I previewed our new edition of Film History: An Introduction, the variety of formats for the book reflects not only changes in technology and the publishing market but also changes in consumer preferences.

However it’s accessed, Film Art: An Introduction still makes us happy. We’ve tried our hardest to help readers understand a bit more about the techniques and effects of cinema. As we point out in the book, thanks to smartphones everybody is a filmmaker now. We think that students’ hands-on experience prepares them for our efforts to understand the creative choices filmmakers have faced from the very beginning.

Thanks as ever to the staff at McGraw-Hill: our editor Sarah Remington and the team consisting of Danielle Clement, Sue Culbertson, Maryellen Curley, Joni Fraser, Ann Marie Jannett, and Elizabeth Murphy. Thanks as well to Kaitlin Fyfe and Erik Gunneson here at the Department of Communication Arts, UW–Madison. And of course thanks to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, and their colleagues at Criterion.

Instructors who want to learn more about this edition can find a McGraw-Hill representative here.

Jeff Smith, who wrote the analysis of Ali: Fear Eats the Soul for our book, also provided an incisive discussion of staging in the film for our series on the Criterion Channel.

There’s a fuller account of how we came to write Film Art in our announcement of the previous edition.

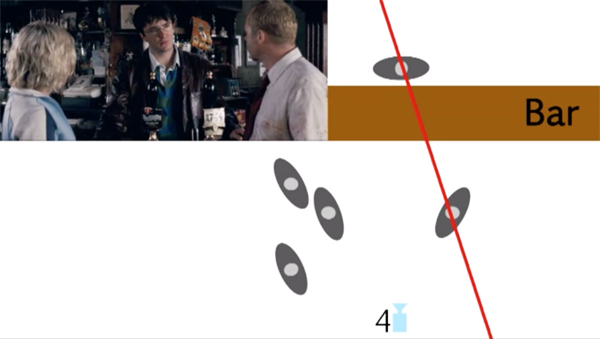

Video supplement: Shifting the Axis of Action in Shaun of the Dead.